Modi’s Diwali extravaganza reveals why we need to tell the numerous stories of Rama

Across India and the international South Asian diaspora, Hindus will be watching on Thursday (Nov. 4) as an elegant event of Diwali– the celebration that marks the birth of the Hindu goddess Lakshmi and the start of a brand-new year in the Hindu calendar– illuminate Ayodhya, a city in northern India believed to be the birth place of the Hindu god Rama.

India’s pro-Hindu nationalist government, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, is arranging a magnificent show to commemorate the legend of the return of Lord Rama to his kingdom with his consort, Sita, and brother Lakshman after overcoming the devil king Ravana. It is believed that the people of Ayodhya lit earthen lamps to invite him, and some 10,000 earthen lamps will be lit this year in Modi’s dazzling screen.

The celebration is as much political in numerous South Asians’ eyes as it is religious. Central to Modi’s long-lasting project of producing Hindu unity is the building of a Rama temple in Ayodhya on a website where, in 1992, Hindu nationalists reduced a 16th-century mosque, claiming it was constructed by the Mughal ruler Babur on the birth place of Rama. In 2019, India’s Supreme Court enabled the construction of the Rama temple.

The topic of a 2,500-year-old Sanskrit impressive Ramayana, written by the sage Valmiki, the legend of Rama is popular not just in India, however throughout southeast Asia. A few days before Diwali, Ramlila– dance-drama shows that enact the life of Rama– are carried out by local stars in rural and city areas alike.

The story has hundreds of variations: In some, Rama is a magnificent hero, and Sita is the virtuous accompaniment– but others have a greatly various informing.

The one that has happened popularized and supported by the Hindu nationalists is from a poem made up by the 16th-century poet Tulsidas, known as Ramcharitmanas. Composed in commitment to Rama, this lyrical poem is a day-to-day prayer chant for lots of Hindus. In this telling, Rama and Sita are the excellent man and woman. The poem forecasts the values of an ideal Hindu household.

Devotees light earthen lamps on the banks of the Saryu River as part of Diwali events in Ayodhya, India, on Nov. 6, 2018.(AP Photo/Rajesh Kumar Singh)But there are some other variations, in which Rama is not the design hero, nor Sita the chaste, virtuous lady. One main Indian ethnic group tells a story in which Sita isseduced by Ravana. In yet another variation, it is Sita who fights and slays the 10-headed satanic force Ravana, when Rama is not able to defeat him.

For another ethnic group, it is Rama’s bro Lakshman who is the protagonist of the story. Various variations of the Rama story are popular throughout Tibet, Thailand, Burma, Laos, Cambodia, Malaysia, Java and Indonesia. In one Thai version of the story, Rama is not the supreme lord, however subordinate to the Hindu god Shiva. In Sanskrit alone, as A K Ramanujan noted in his popular essay on the “Many Ramayanas,” there are about 25 or more tellings of the Rama story.

Other South Asian religious traditions likewise commemorate the five-day celebration, which started this year on Tuesday.

For Sikhs, Diwali is a time to commemorate the release of Guru Hargobind, the sixth of 10 spiritual leaders, who was locked up by Jehangir, an emperor in the Mughal dynasty that ruled the Indian subcontinent from 1526 to 1857.

As a Jain, I fill my house with the light of earthen lights to welcome Lakshmi, the Hindu goddess of success, who, Hindu mythology holds, was born on Diwali during the churning of the cosmic ocean. I also meditate on Mahavira, the 24th spiritual instructor of the Jain course, to celebrate his achieving “nirvana,” or enlightenment, on this day.

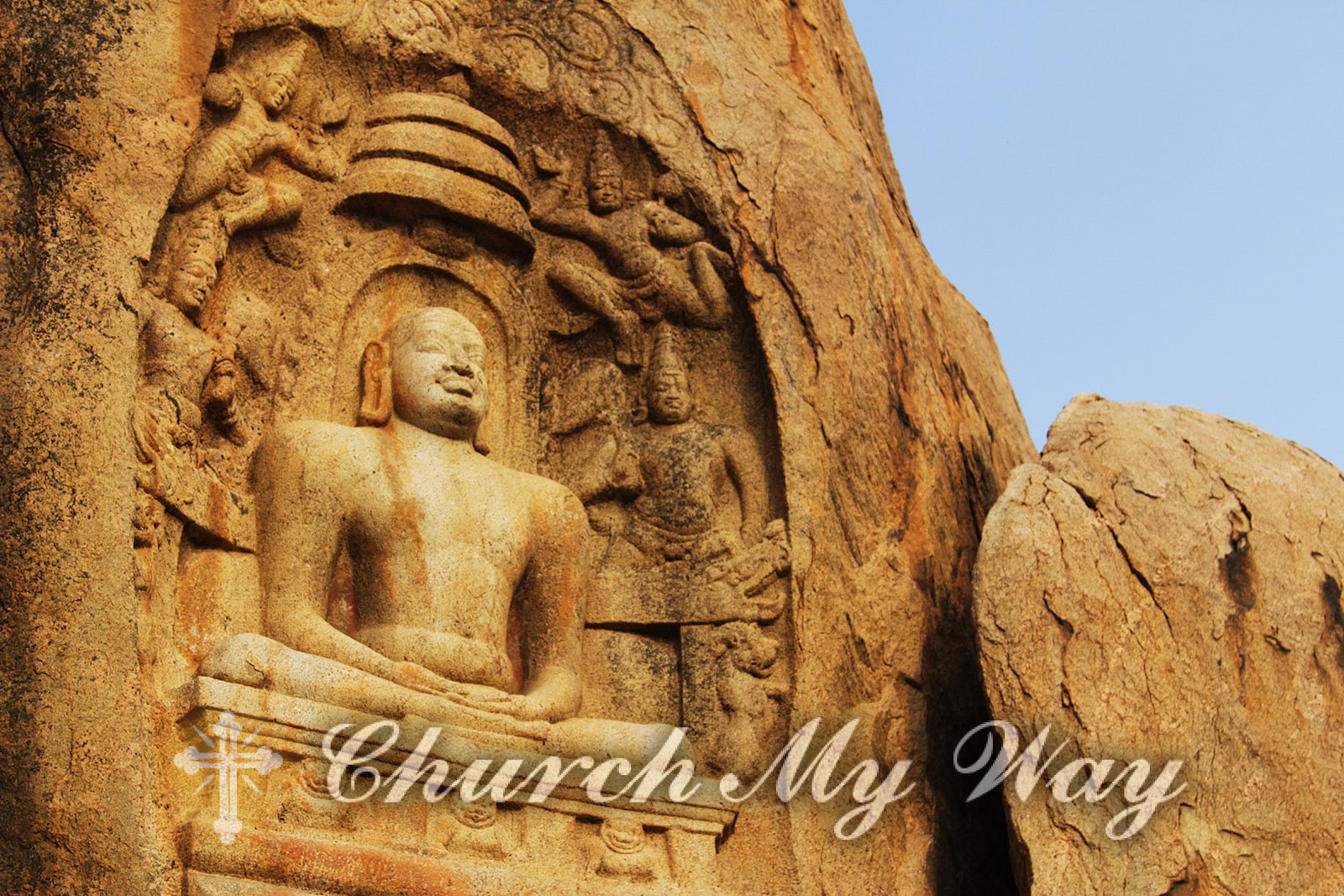

Carving of Vardhamana Mahavira, the 24th and last Tirthankara, in the Samanar Hills of India. Photo by Francis Harry Roy S/Wikipedia/Creative Commons The Jain literature includes at least 17 different tellings of the Diwali story. In one of the earliest I recognize with, both Rama and Ravana are evolved souls, on the course of knowledge. Rama does not devote violence– so he does not kill Ravana.

“The Ramayana in India is not just a story with a variety of retellings; it is a language with which a host of declarations might be made,” writes another scholar, Velcheru Narayana Rao. He explains how women in India’s southern state of Andhra Pradesh sing the Ramayana to express their feelings. The tunes change depending on who is singing: The Ramnami Samaj, a sect of lower-caste Ram devotees, remove the verses which contain referrals to Brahmins and lower castes.

Some Hindus fear that this abundant diversity is gradually being eliminated as Hindu nationalists seek to create a typical Hindu canon in events like the Ayodhya celebration. Cultural unity has actually been the Hindu nationalist goal ever since it emerged in the early 20th century, under British colonial rule. One of the most popular functions of Hinduism, the defense and sacredness of the cow, belonged to this creation of a typical significance under which the varied hairs of Hinduism could discover commonality.

This Diwali, as numerous in the diaspora and across the world invite the goddess Lakshmi, they will not do so without worshipping Ganesha, the God of wisdom and discernment. And that is necessary to note, along with the many stories of Rama.